21 A Changing Society, Mitsui’s Agony

Fire and Riots

Mitsui faced many daunting internal and external challenges in the early modern period. Destructive fires were the destiny of cities with large numbers of close-set wooden buildings. Mitsui built numerous storehouses with thick earthen walls that were effective against fire, and drew up detailed preparedness plans. Although they sometimes took advantage of the burning of rival shops, fire was a continuing cause of suffering throughout the early modern period, as a shop might no sooner be rebuilt than it was destroyed by another fire. In the Great Tenmei Fire of 1788, the Kyoto residences of every Mitsui family and Mitsui shop burned to the ground. In addition to many shops and residences, Mitsui held large amounts of real estate in the cities as collateral for the shogunate’s public funds, meaning that losses not only to fires but also great earthquakes were frequent.

The latter half of the early modern period also saw an increase in the numbers of poor living in large cities. Failed harvests brought famine, and as food prices exploded, wealthy merchants were often victims of smash and grab riots by those who were desperate to survive. While Mitsui had been able to escape the mobs’ wrath, in 1837 a shogunate official, Oshio Heihachiro, was unable to bear the suffering of the poor and incited an uprising in which the whole of Osaka kimono shop was destroyed by fire, and many were injured by bullets from the guns.

Debts and Discord in the Mitsui Family

Mitsui Takatoshi’s sons worried about the next generation of the family pursuing lives of idleness and luxury. They were also concerned to avoid strife within the family. In a series of regulations issued in the early 18th century (→08,09), they emphasized frugality, industriousness, and harmony. But in later eras, some families continued wasteful practices that exceeded their allocation of funds from the Omotokata (→10) and accumulated significant debts. This, in combination with the pressures of difficult business conditions (→12,17), became a source of discord in the Mitsui Domyo. From 1774 to 1797, with Mitsui facing a business crisis, the principle of solidarity (Shinjo Itchi,→09) was abandoned and the 11 families and their businesses divided into three groups (→10). The split was concealed from outsiders, but this created problems in relations with the shogunate and with the Kishu Tokugawa family. Ultimately, several senior members of the Mitsui Domyo were punished for this lack of transparency.

During the 1820s, the debts of certain senior members of the Mitsui Domyo ballooned to the point where the shogunate’s Kyoto magistrate and the Kishu Tokugawa family stepped in to resolve the situation.

The Omotokata and senior managers from all side of the business worked to prevent a similar situation from recurring (→Fig. 21b), but a thoroughgoing solution was difficult to achieve.

Financial Extortion

The greatest source of pain for Mitsui in the early modern period was financial extortion on the part of daimyos and the shogunate. After enjoying more than two centuries of peace, Japan’s economy had developed extensively, and merchants like Mitsui had accumulated astonishing wealth. The shogunate and the daimyos relied for their income on rice taxes levied on farmers. But even when such taxation proved insufficient, the profits of the merchant class were left untaxed. Instead, the shogunate and the daimyos used a variety of methods to commandeer these profits for their own benefit. One such method was financial extortion (goyokin). A wealthy merchant would be suddenly ordered to disgorge a considerable sum of money-ostensibly as a loan that accrued interest and was to be repaid over time. But given the financial difficulties faced by the recipients, such loans were often never fully recovered.

Whenever the Kishu Tokugawa family (→18) found itself in financial straits, they would extort funds from Mitsui. A lord’s request was difficult to refuse, and by 1769, the Kishu Tokugawa’s accumulated debt to Mitsui had climbed to 360,000 ryo, equal to almost 40% of Mitsui’s total capital. These debts were written off as uncollectable under the Anei Partition (→10), but the Kishu Tokugawa continued to squeeze several tens of thousands of ryo from Mitsui under a variety of pretenses.

Extortion by the shogunate mostly occurred when it needed to manipulate prices in the rice market. Such interventions began in 1762, and among the shogunate’s targets for extortion, Mitsui was forced to surrender the largest sum, 50,000 ryo. In the early 19th century, the shogunate’s debts amounted to almost 5,000 kan of silver. In 1843, the shogunate tapped Mitsui for another 10,000 ryo. Such extortion was difficult to anticipate as well as to refuse, and when funds set aside for contingencies were insufficient, Mitsui had to scramble to gather the funds while delaying their transfer to the shogunate for as long as possible. It was sometimes even necessary to draw down working capital, which put a huge strain on the business (→17). At the end of the Edo period, the shogunate, in need of a huge amount of money, even extorted a cumulative total of 500,000 ryo from Mitsui.

The Importance of Information

Mitsui paid close attention to policy formulation by the shogunate, as well as to events across the country such as major disasters. Soon after the business was founded, it was collecting and recording information all the way from Ezo (today’s Hokkaido) in the north to Satsuma (today’s Kagoshima) in the south (→Fig. 21c).

In the 19th century, pressure from the great powers to open Japan, which was the harbinger of a new era, began to feature prominently in Mitsui’s records.

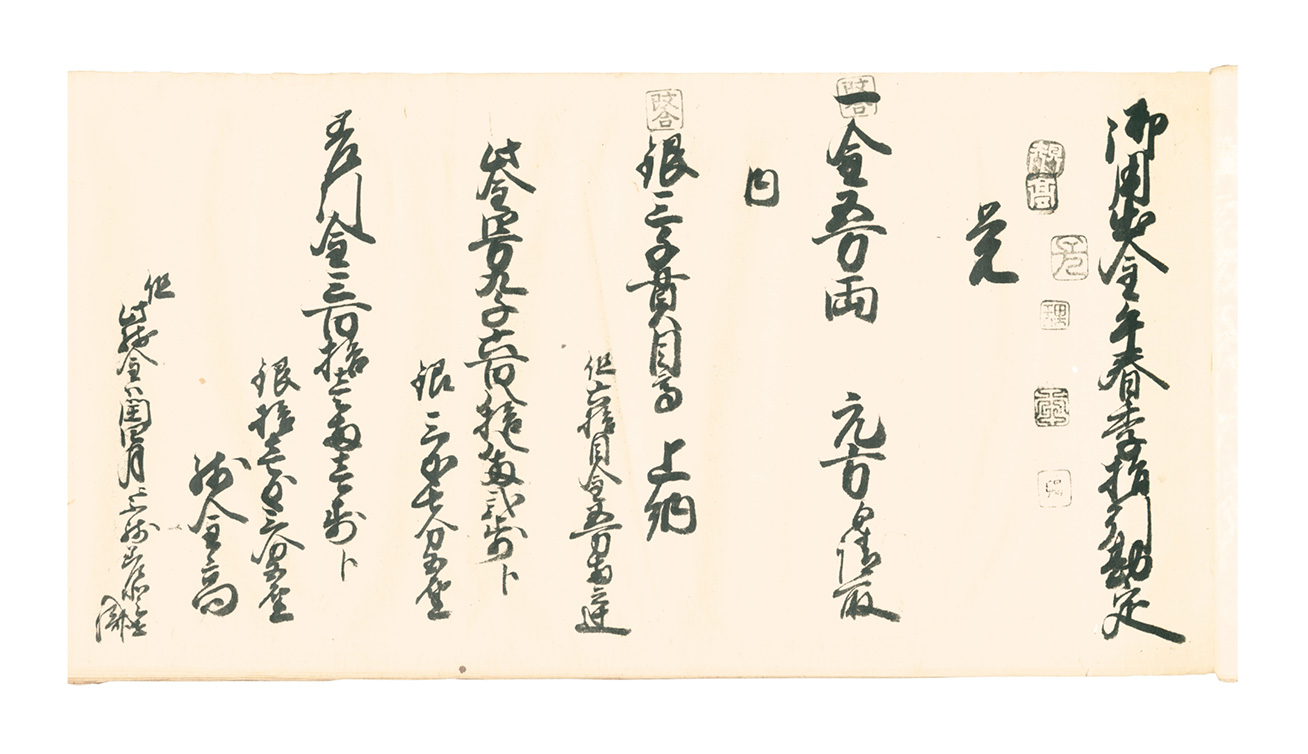

A bundle of letters from the Osaka kimono shop to the Kyoto kimono shop. During the early modern period, Mitsui maintained close communication between its shops in Edo, Osaka, Kyoto, and Matsusaka using frequent written messages. The letters present a detailed picture of directives from the Kyoto kimono shop, which exercised overall control, as well as the state of the business, management decisions, and other matters.

Communications sent on a regular basis were numbered in sequence and referred to as numbered letters (banjo). Other letters were left unnumbered (mubanjo). Letters were bundled for preservation (sashi), and an enormous number of these communications has survived. The Horeki financial extortion mentioned here was ordered by the Osaka magistrate office to the Osaka kimono shop, so the situation was reported from the Osaka kimono shop to the Kyoto kimono shop, which had the supervising function.

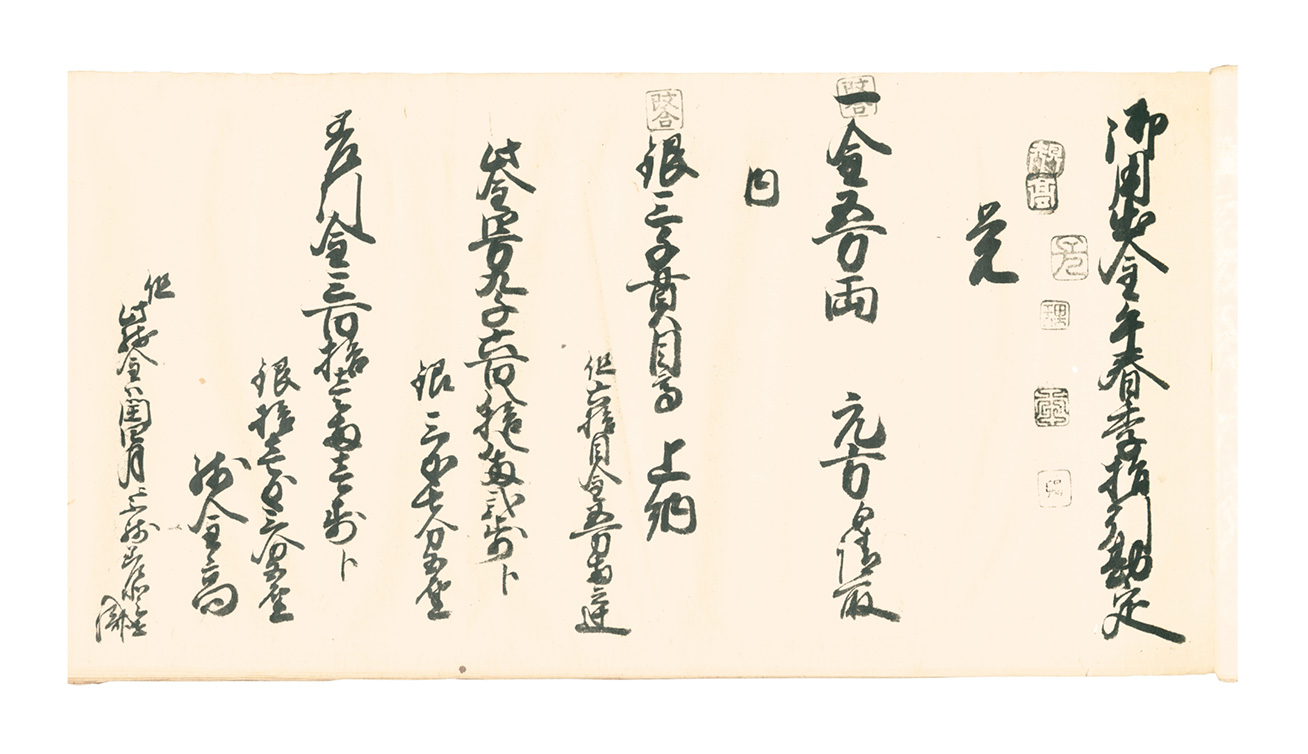

Description

This is a part of report sent from the Osaka kimono shop to the Kyoto kimono shop. It is a report regarding financial extortion payments made to the shogunate during the first half of 1762. It states that the huge payment of 50,000 ryo demanded by the shogunate was received from the Omotokata, and that nearly all of that amount-3,000 kan of silver-has already been remitted to the shogunate, leaving 311 ryo to be paid.

This was the first major instance of financial extortion on the part of the shogunate. It reflected the extent of Mitsui’s accumulated wealth, and presaged a bitter struggle to cope with new shogunate policies.

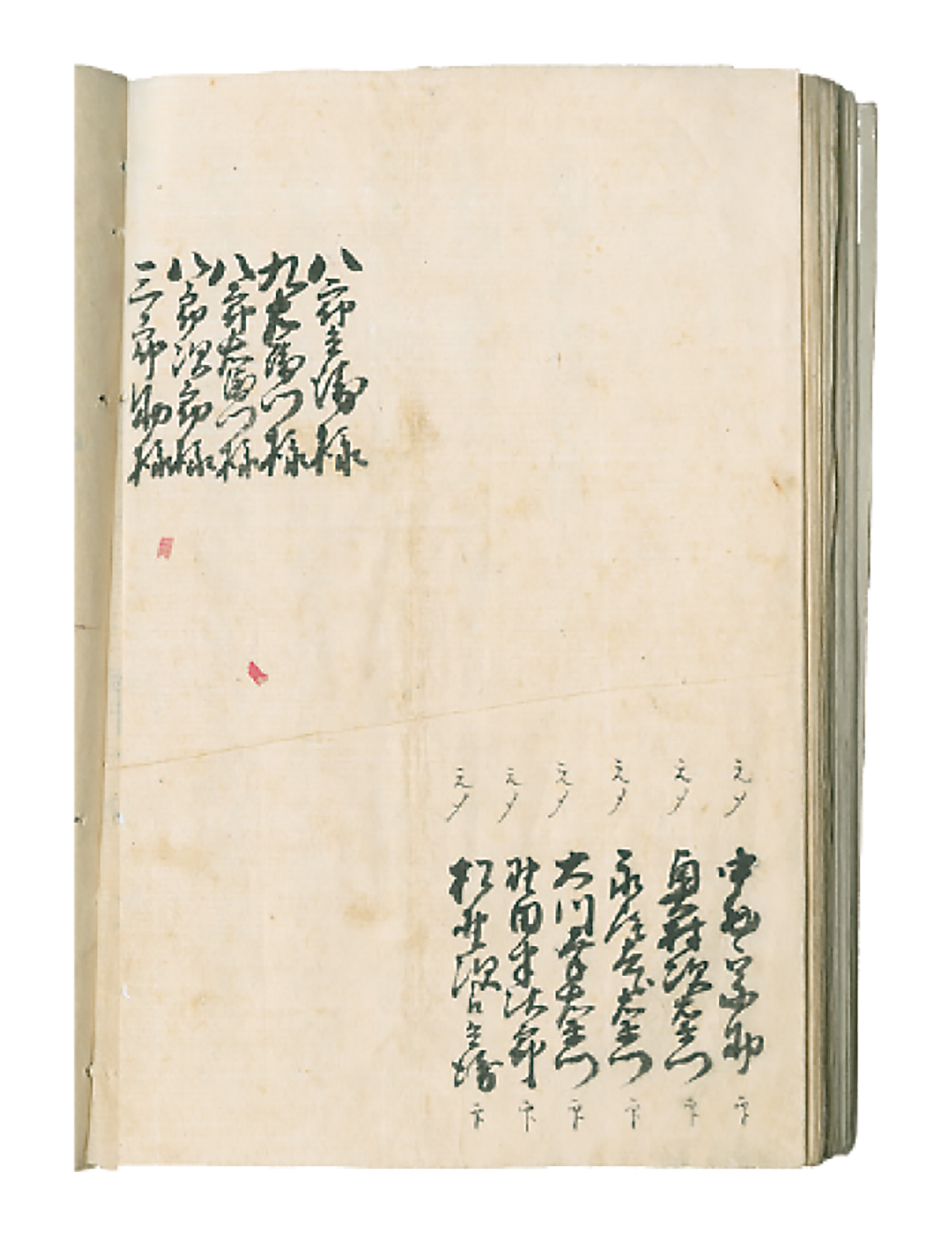

A petition signed by eight senior employees to Mitsui Domyo, stating their opposition to the Anei Partition of 1774.

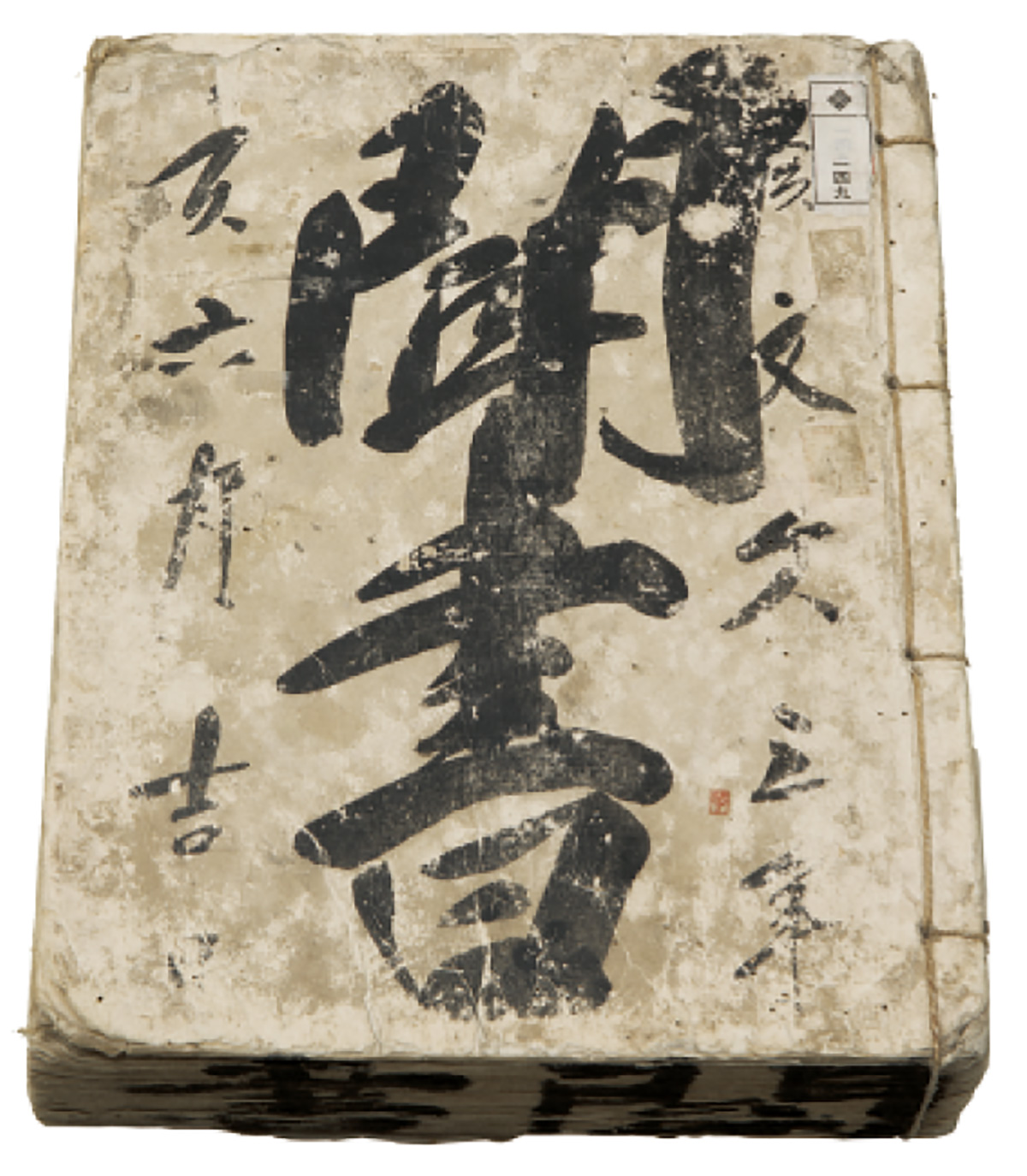

A record from the Osaka money exchange store containing major news items such as political disturbances and large-scale disasters as well as trending rumors, with corresponding sources of information. This record is from the late Edo period.