18 Money Exchange Stores (3): Feudal Lords

Currency Reform

In the early modern period, the shogunate maintained a monopoly on the issuance of currency. As Japan’s precious metal deposits were being exhausted, demand for currency was increasing along with economic growth. Too, the shogunate’s finances were suffering from structural problems and deteriorating. To address these challenges, the shogunate frequently expanded the money supply by recoining the currency to a lower precious metal content (→Fig. 18b).

Mitsui was often required by the shogunate to exchange new for old currency in the Big Three cities. Of particular importance to Mitsui were the currency reforms implemented in 1736, which occurred after years of economic stagnation (→08). To encourage people to surrender their old coins, the shogunate allowed them to be exchanged for new coins at a premium to face value, while also allowing Mitsui to reap significant profit. Commission income from currency exchange was huge; in addition, a policy of collecting old debts denominated in old currency wherever possible resulted in further significant profits (→17). The economy subsequently improved, and the kimono fabric division increased sales rapidly (→12), making this currency reform a business milestone for Mitsui.

At the same time, there were instances where recoinage had no merit, such as the recoinage that began in 1818.

Lords and Benefactors

The Mitsui family constitution Sochiku Isho (→09) stated that loans to feudal lords were to be avoided, but stipulated that the Kishu Tokugawa family, who ruled Matsusaka, and the Makino family, who were benefactors of Mitsui, would receive special treatment. In fact, Mitsui continued to fund both families throughout the early modern period. The Kyoto exchange store handled the funding, with approval from the Omotokata (→10).

At first, both families paid their loan installments regularly, and the arrangement was beneficial for Mitsui as well. But by the mid-18th century, both families’ finances began to deteriorate, as was the case with most feudal lords. Loan repayment stagnated, and the families made additional large loan requests. In anticipation of possible default, Mitsui had not booked interest payments from both families as income, instead treating it as a reserve. Once the amount of payments in arrears became too large, it could be written off as a nonperforming loan, or the terms of repayment modified, but the arrears for the Kishu Tokugawa family in particular continued to grow (→21).

Beginning in 1822 in Matsusaka, Mitsui became involved in the issuance of paper currency by the Kishu Tokugawa family (→Fig. 18c). The outstanding amount of such currency continued to rise until the end of the shogunate.

High-Ranking Shogunate Officials

While Mitsui tried to avoid making daimyo loans, they treated high officials of the shogunate differently. Mitsui was especially attentive to the need for funds on the part of the shogun’s senior councilors, who played an important role in managing the shogunate, as well as officials controlling western Japan, such as the governor-general of Kyoto (Kyoto Shoshidai) and the keeper of Osaka Castle (Osaka Jodai), and the magistrates (machi bugyo) of Kyoto and Osaka. It is likely that Mitsui did this not so much to realize profit, but in view of the close relationships it maintained with these officials as an official merchant purveyor to the shogunate.

Aristocratic Priests and the Imperial Palace

In 1745, the Rinnoji-no-miya-the aristocratic priest responsible for Nikko Toshogu Shrine and Ueno Kanei-ji Temple, where Tokugawa family mausoleums were located-allowed Mitsui to manage his assets. In theory, these loans were legally guaranteed under the name of temples and shrines, but in reality, Mitsui lent large amounts of its own funds. This was similar to the system of exchange services purveyed to the shogunate (→16), and was an important business activity for the Edo exchange store.

In addition, as an official merchant purveyor to the shogunate, Mitsui was involved in numerous funding activities relating to the imperial family, such as defraying the reconstruction costs of imperial properties after fires and other disasters. Mitsui also served as official merchant purveyor to the imperial family (→Fig. 18d), and the head of the Kita family even served in a very junior position in the imperial bureaucracy. While direct contacts with the imperial house were minor and limited, this would be reevaluated after the Meiji Restoration took place.

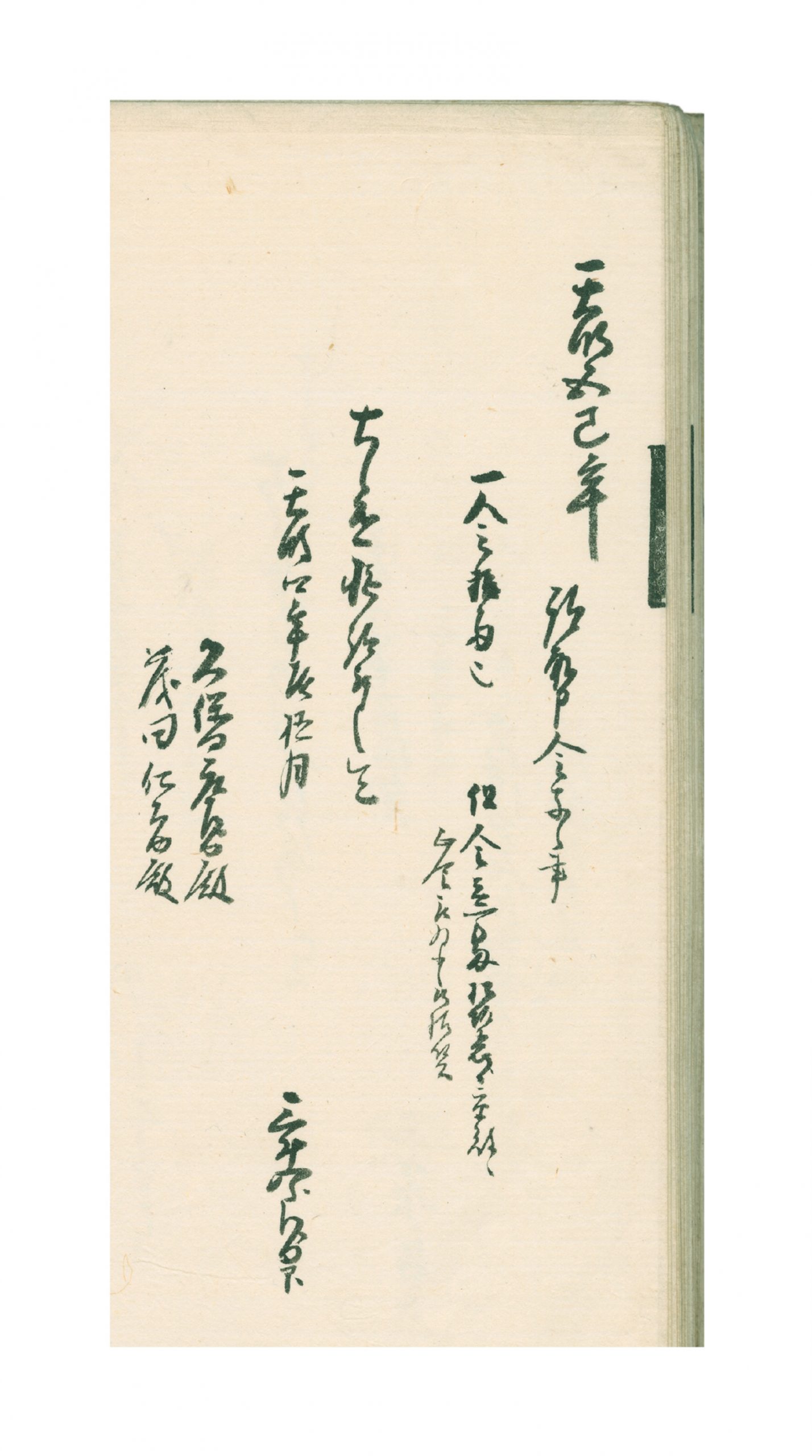

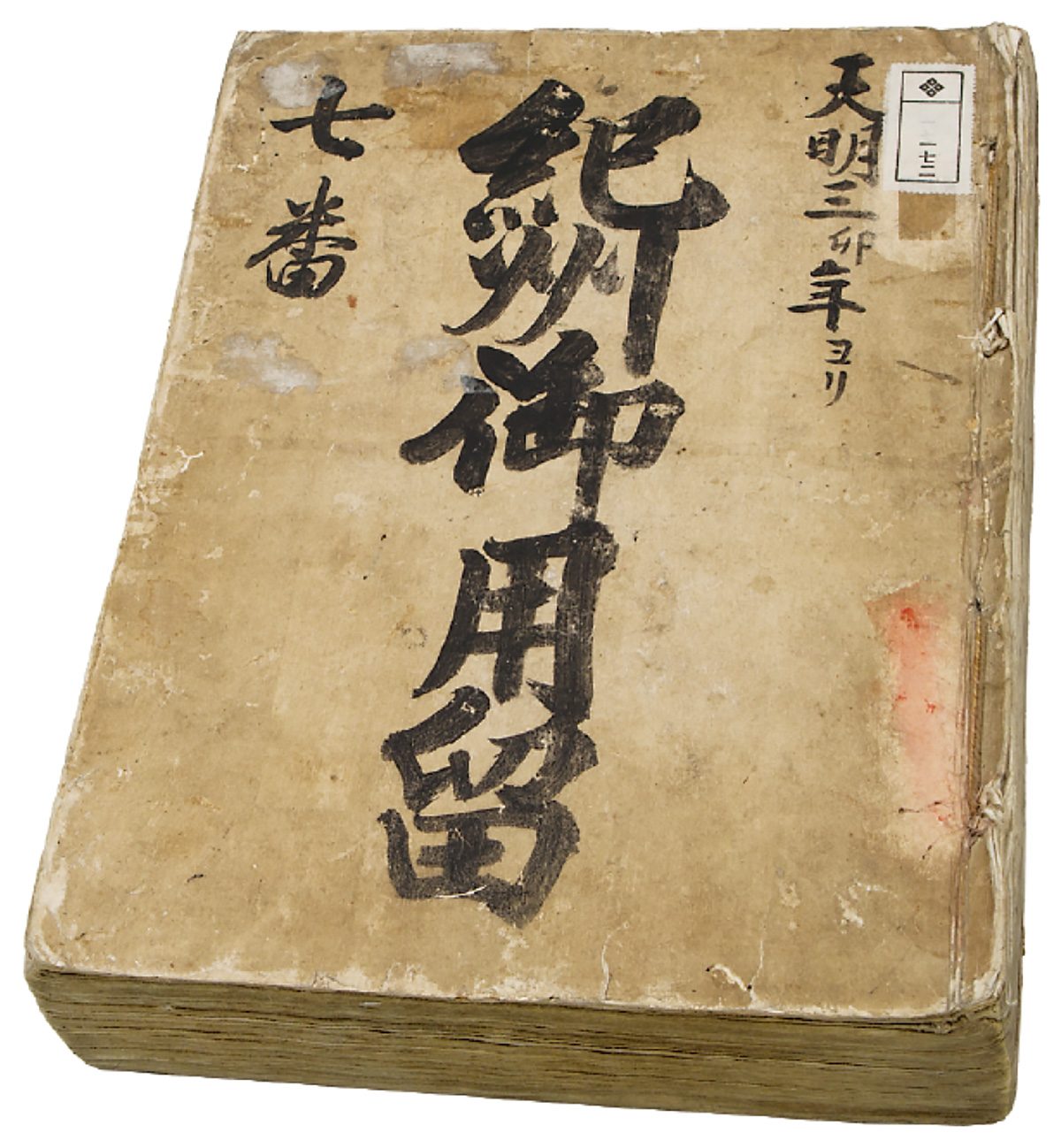

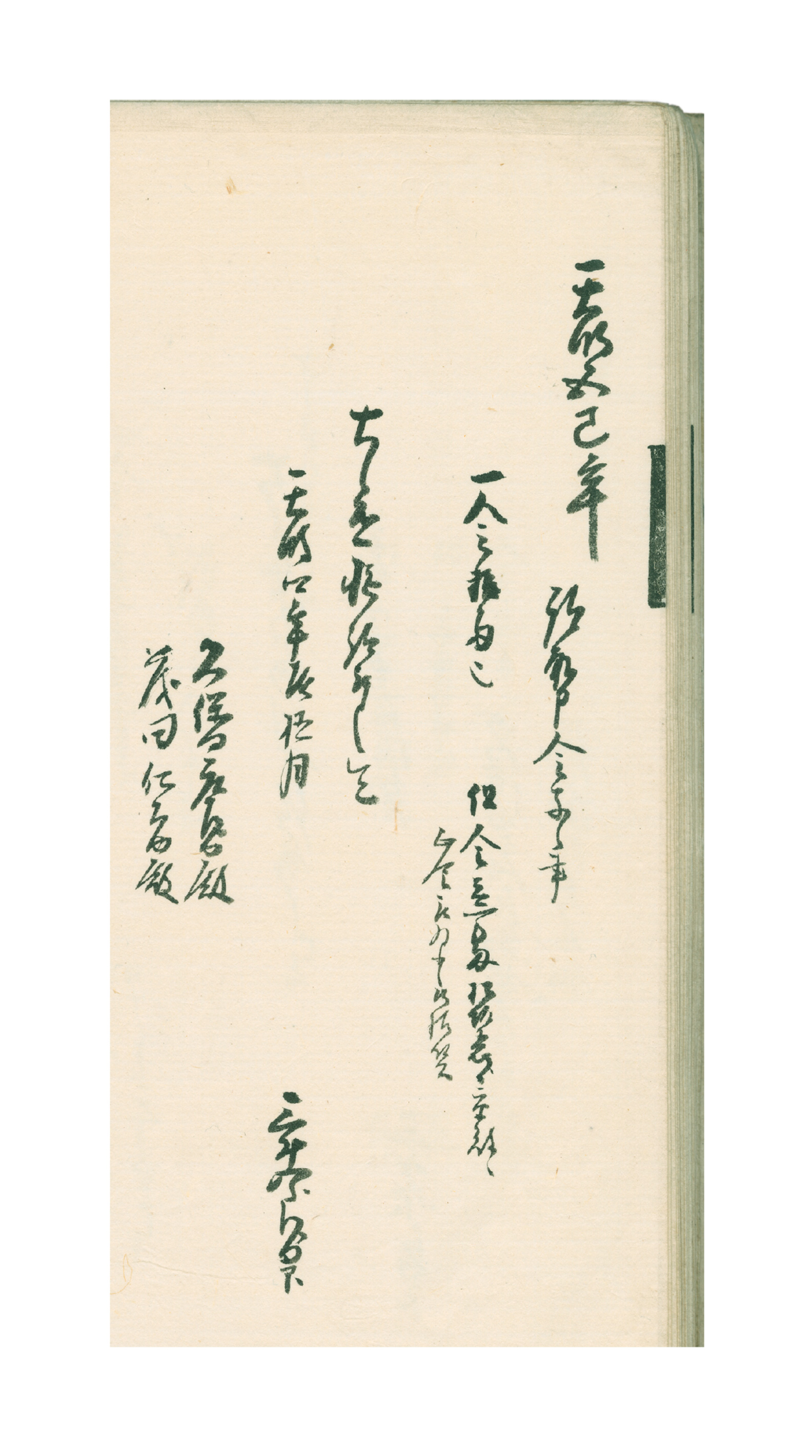

The Kyoto exchange store kept daily records of its dealings with the Kishu Tokugawa family. Records exist for the period 1783 to 1870; earlier records were lost in the great fire that burned Kyoto in 1788 (→21). The seventh volume of the records, the oldest one in existence, is shown here. Such records were kept on permanent file at the Kyoto exchange store.

In addition to the shogunate, Mitsui’s financial division had dealings with many feudal lords, and many records remain, sorted by individual customer.

Description

This page of the record is a copy of a receipt issued to an official of the Kishu Tokugawa family in December 1784 (lunar calendar). The receipt is in the name of Mitsui Hachiroemon (then Takasuke, sixth head of the Kita family), and states that ten ryo was paid to Mitsui as a fee for transporting 10,000 ryo from Matsusaka, in the Kishu domain, to Kyoto. That same year, Princess Yoshi of the Kishu Tokugawa family married Ichijo Teruyoshi, Minister of the Right, and it is thought that the cash transported was used to fund the wedding as well as construction of a new residence. At the same time, the Kishu Tokugawa family applied for a loan of 13,000 ryo. This was approved by Mitsui after negotiating the amount down to 9,500 ryo.

This page of the record is a copy of a receipt issued to an official of the Kishu Tokugawa family in December 1784 (lunar calendar). The receipt is in the name of Mitsui Hachiroemon (then Takasuke, sixth head of the Kita family), and states that ten ryo was paid to Mitsui as a fee for transporting 10,000 ryo from Matsusaka, in the Kishu domain, to Kyoto. That same year, Princess Yoshi of the Kishu Tokugawa family married Ichijo Teruyoshi, Minister of the Right, and it is thought that the cash transported was used to fund the wedding as well as construction of a new residence. At the same time, the Kishu Tokugawa family applied for a loan of 13,000 ryo. This was approved by Mitsui after negotiating the amount down to 9,500 ryo.

From left: koban coins from the Genroku, Shotoku, Genbun, and Bunsei eras. The value in each case is ostensibly one ryo, but the gold content differs from coin to coin. The Shotoku koban is a high-quality coin with high gold content. The gold content of the other koban is lower, to allow more to be coined. Other gold and silver coins were also melted down and reissued repeatedly.

This clan currency was issued by leading Matsusaka merchants, including Mitsui at the behest of the Kishu Tokugawa family. The notes are backed by merchant guarantees to redeem them for silver coins. From right, face values of one monme, five bu, three bu, and two bu of silver (one monme = 10 bu). Notes equal to 64 monme could be exchanged for one ryo in gold. These notes were trusted, and ultimately circulated more widely than anticipated.

Wood cards such as these denoted status as an official merchant purveyor to the shogunate. The card on the top left signifies purveyor to the Kishu Tokugawa family, and the one on the lower right signifies purveyor to the imperial house, as denoted by the crests of wild ginger trefoil and chrysanthemum respectively. The long handle shown can be detached. Official merchant purveyors might also have lanterns, fabrics, and other objects bearing the crests of their customers.