08 An Age of Crisis and Record Keeping

The Kyoho Reforms and an Economic Downturn

The late 17th century-the age in which Takatoshi passed away-saw a growth in the use of currency and the continuation of inflationary trends. Mitsui, too, rode this out as it developed further. However, owing to persistent criticism over rising commodity prices and the like, in the 1710s the shogunate undertook a recoinage to reduce the volume of currency in circulation. The situation that followed was deflation. A severe economic downturn in urban areas resulted under the Kyoho Reforms enacted by the 8th shogun Yoshimune that followed. Commodity prices were reduced, bans were imposed on extravagance, and restrictions were put into place on litigation related to debts.

Low Rice Prices, High Commodity Costs

During this time, the climate was temperate, harvests were abundant, and the price of rice-the most important product in early modern Japanese society-was low. However, the prices for commodities that previously had run in parallel with those for rice now rose, and this had become a major issue. The situation had a direct impact on the finances of the daimyo, who had been converting their annual rice tributes into money in order to purchase consumer goods. They were also hit with a serious famine in western Japan due to an onslaught of planthopper pests. The great merchants who had been lending enormous amounts of funds to the daimyo fell into ruin one after another.

Changes to Management Style

At Mitsui, the children of Takatoshi and the prominent figures of the early years were passing away one after another, and it found itself faced with crises both internally and externally. The Mitsui Domyo and their employees took the downturn seriously, and they sought ways to overcome it through frugality and in their business.

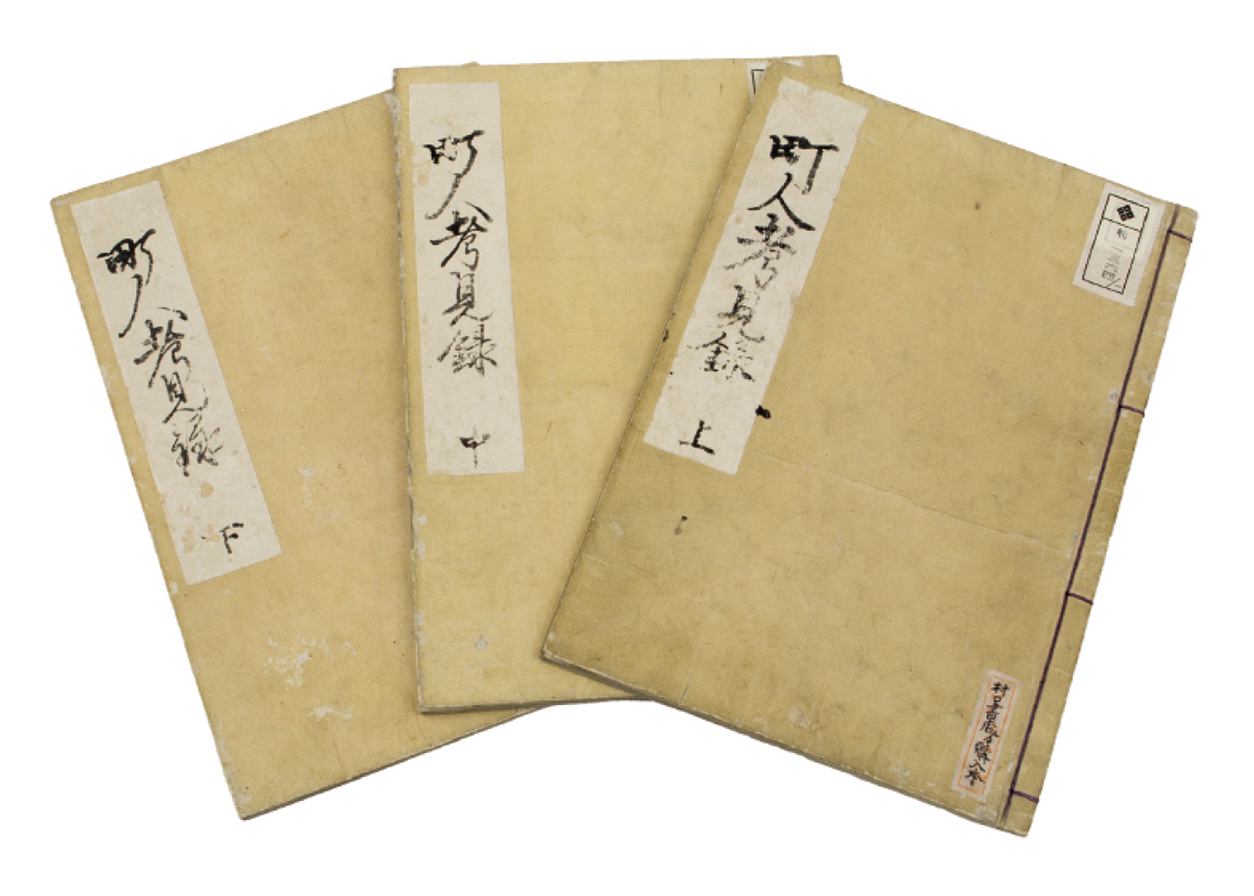

The Chonin Kokenroku (→Fig. 08a) created during this period is thought to have been meant to serve as a means for educating the younger generations amid the downturn. An extremely prudent management style is apparent from the language used to explain the abundant examples of failures. It shares in common with the Sochiku Isho (→09) family constitution written around the same time in the form of Takahira’s last will and testament such points as a warning against businesses that offer high profits but come with risks, adhering to traditional business lineups, an emphasis on cash holdings, and a warning against extravagance from having accepted the official purveyor’s charter.

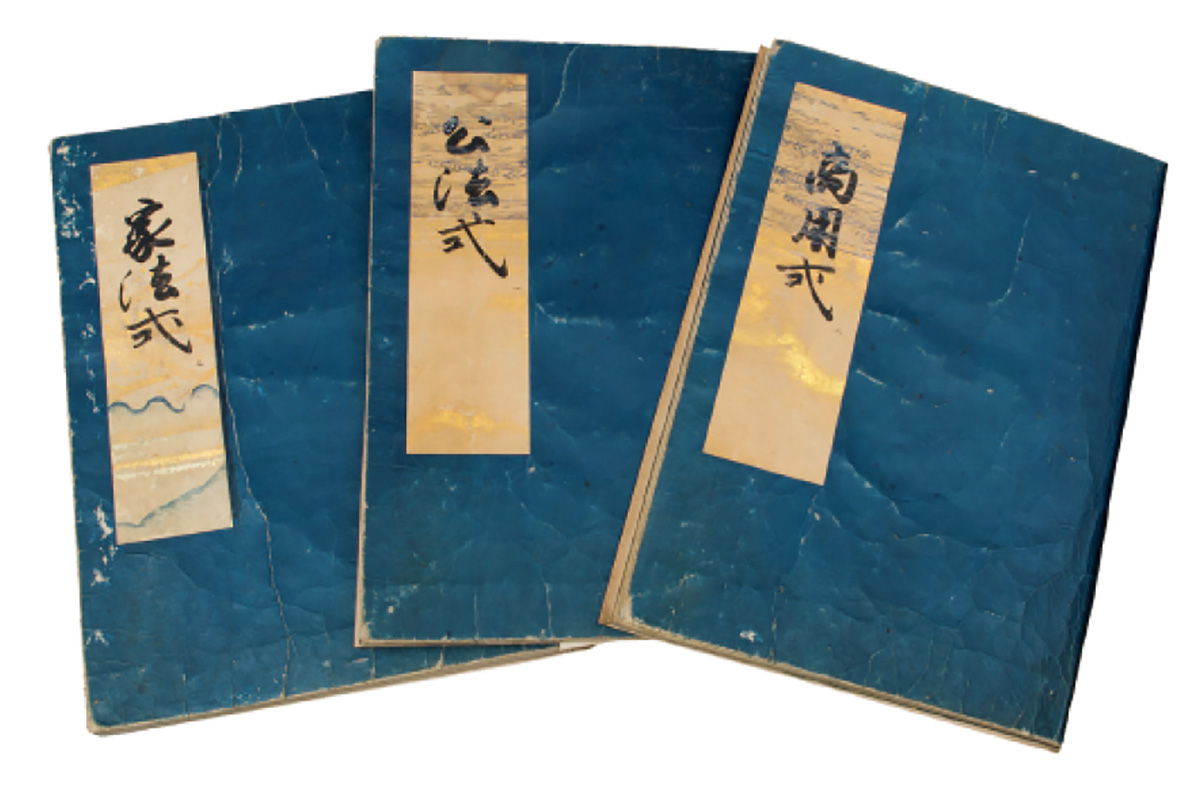

The Codification of Rules and Maintaining a Documentation System

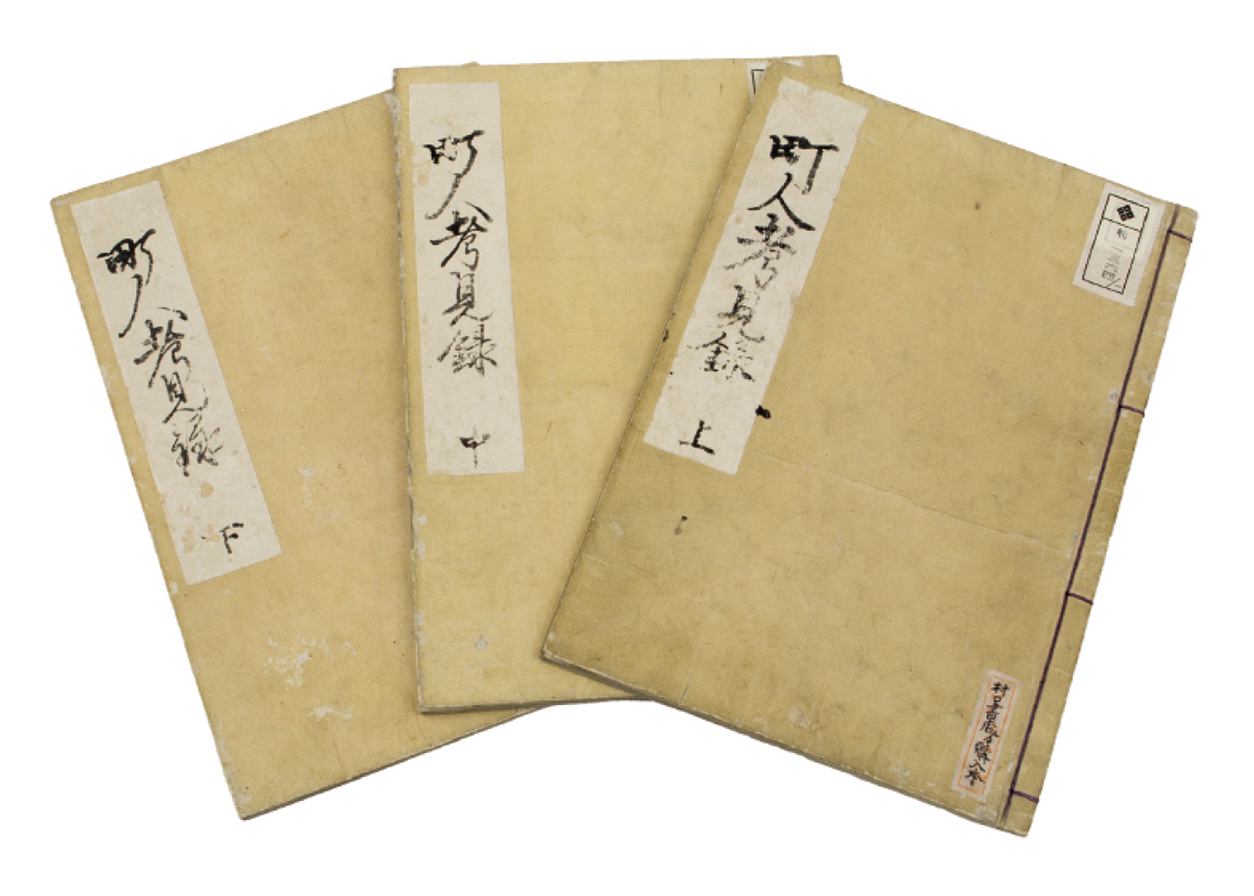

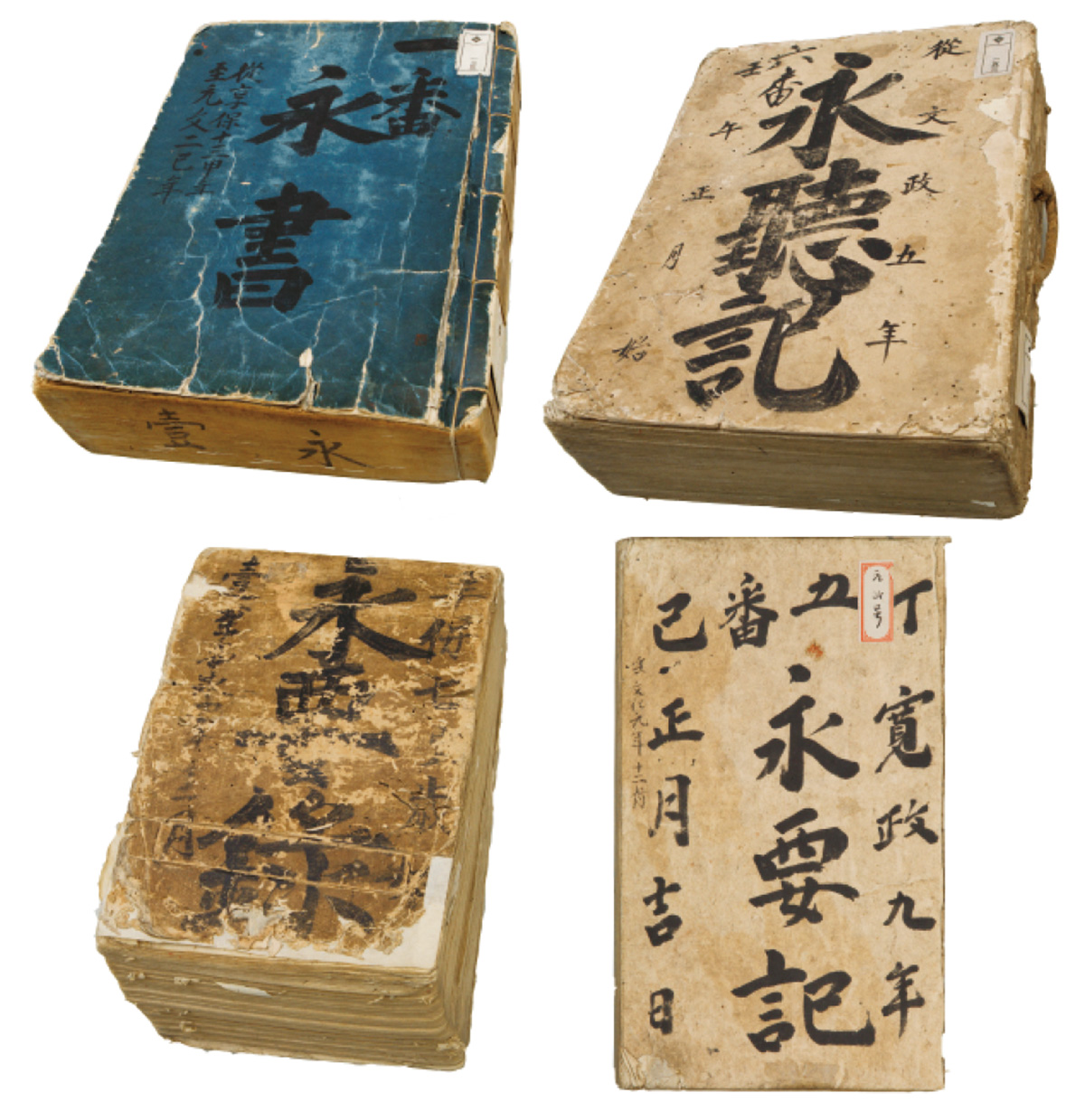

During this period, numerous other family histories and shop rules were also created, setting the standard for those to come (→Fig. 08c). Sales documents were also systematized. The many records (→Fig. 08d) written and passed down through the early modern period begin during this period.

Other great merchants were similarly setting down their own family constitutions and rules, such as the Konoike family, mentioned in the commentary for Chonin Kokenroku; the Shimomura family, famous for its prominent kimono store Daimaru (→14); and the Sumitomo family, known for its copper mine operations. Such developments could be seen throughout society, including within the shogunate. In this age of crisis, merchants and others were going back to the history and ideas of their ancestors to work toward unity, while also codifying solid stance that they would leave behind for their descendants.

The Start of Compiling Histories

Furthermore, histories of the past were researched and recorded. The goal was to pass them on to generations who would have had no contact with Takatoshi, and who had no experience of the hardships in the business’ founding and development. Documents from the founding years were sorted out (→02), old top managers were instructed to submit memoranda (→03), and both the Kadenki (→02) and Shobaiki (→04) were compiled. Research on distant ancestors also began. This may be described as the first period of compiling and editing histories for Mitsui. The history of the early years known to us today is largely based on the records that were organized and created in this era.

Written by Takafusa, third head of the Kita family (→Fig. 08b). Completed in 1728. The book is based on interviews with Takafusa’s father Takahira (→06), compiling various stories about the businesses and collapses of some 50 merchant families that had fallen into ruin. The work also includes various aphorisms and exhortations. It was put together on the recommendation of a prominent early employee, Nakanishi Sosuke (→07).

The storyteller Takahira was in his late 70s at the time, and there are sections in which he talks about matters from decades before based on his memories. Be that as it may, when it comes to commerce during the dawning years of the early modern period from which detailed records are scarce, it is regarded as an extremely valuable historical document observed by a prominent merchant who had experienced actual business conditions for many years. Copies were already circulated widely since early modern times. The copies presented here bear the signature and seal of Takafusa at the end, and were used as the source text for the material excerpted in Nihon Shiso Taikei, a collection of Japanese thought compiled by the Japanese publisher Iwanami Shoten.

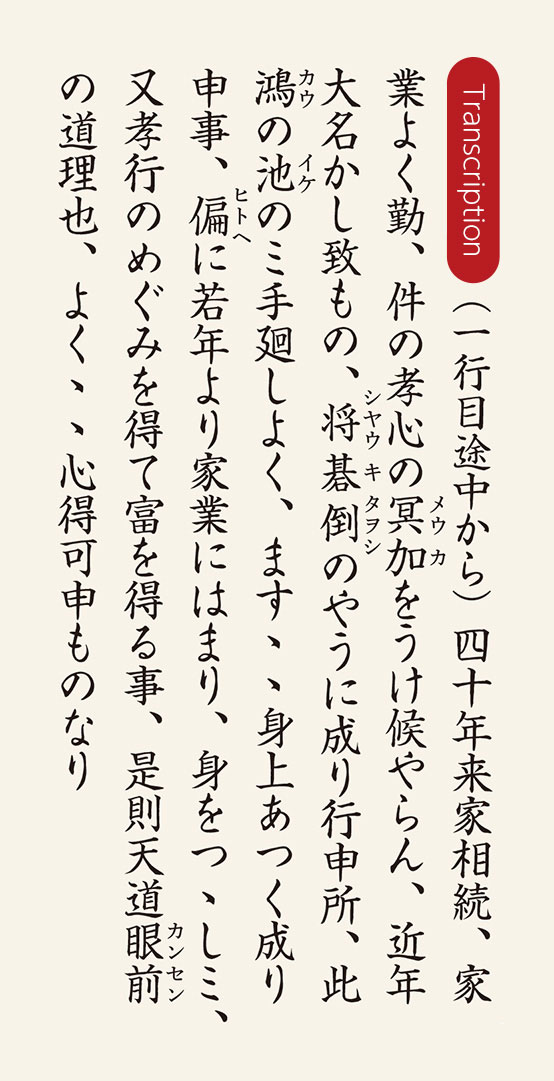

Chonin Kokenroku (an investigatory record concerning merchants brought to ruin)

Translation

The money-exchanger Konoike Zenemon for forty years had a house, worked hard at the family business, and demonstrated filial piety. Perhaps it was due to his meritorious deeds, but while merchants who given loans to daimyo in recent years have been falling into ruin like dominoes, Konoike alone excelled at being diligent and grew more and more affluent. Devoting oneself to the family business wholeheartedly from a young age, behaving prudently, and acquiring wealth through meritorious deed of filial piety is correct as the path that one should follow. This is something that should be borne well in mind.

Description

Coming after having taken up numerous examples of merchants who had fallen into ruin, this passage instead offers as a good example the case of Munetoshi, the third head of the Konoike family (the roots of Nippon Life Insurance and Sanwa Bank) who were great Osaka merchants working like the Mitsuis in the money exchange business.

Third head of the Kita family. The eldest son of Takatoshi’s eldest son. Following the death of his father Takahira, assumed the position of oyabun (“boss” or “head”) (→09) who oversaw the entire family. He had many children, and added two families to the female lineages (→06). He was also skilled in such arts as tea, perfumes, painting, and poetry.

Document collections compiling working conditions for employees, the rules employees are to follow, and points to consider in commerce. The editors sorted through and selected from rules that had been issued up to that point, and recompiled them into these works. These specific collections were for the kimono shops, and they would be read out to employees in January, May, and September of the lunar calendar. Numerous other collections of rules were also created during the same era.

Eisho, from the Kyoto kimono shop (upper left); Eichoki, from the Edo kimono shop (upper right); Eiyoroku, from the Kyoto money exchange store (lower left); and Eiyoki, from the Edo money exchange store (lower right). Records meant to be preserved in perpetuity (the character for “ei” in each title means “eternal” or “perpetuity”), written to be passed down at each shop.