20 Employees (2): Daily Life and Management

Employee Daily Life

The daily lives of live-in (sumikomi) employees were highly regimented. The Kyoto kimono shop gave employees around ten days off each year. Entertainment was limited: viewing cherry blossoms in April, enjoying the Gion Festival and evening breezes off the Kamo River in July, and watching kabuki performances in November, among others. Festivals to honor Ebisu, the god of commerce, were held in the New Year and October, and personnel changes were also announced in the New Year.

Meals were simple, mainly rice with one soup and one side dish. Employees could enjoy moxibustion treatment in summer and winter to recuperate and recharge. Nevertheless, there were frequent deaths due to illness. In the early 18th century, a common grave was established for employees. Mitsui’s early modern exchange stores strived to minimize costs, such as for food, and the number of employees declined because of deaths or resignations due to illness. In fact, such reductions in headcount were a factor in the favorable business performance of the financial division (→17).

Little is known concerning the daily life of the manservants.

A Vast Number of Rules

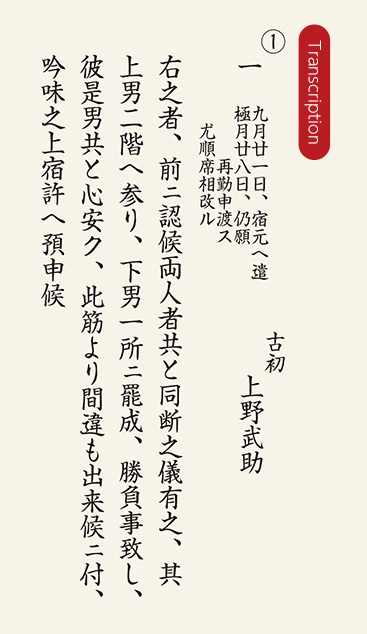

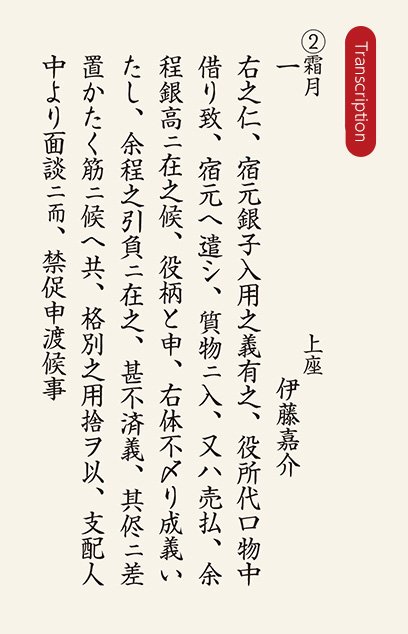

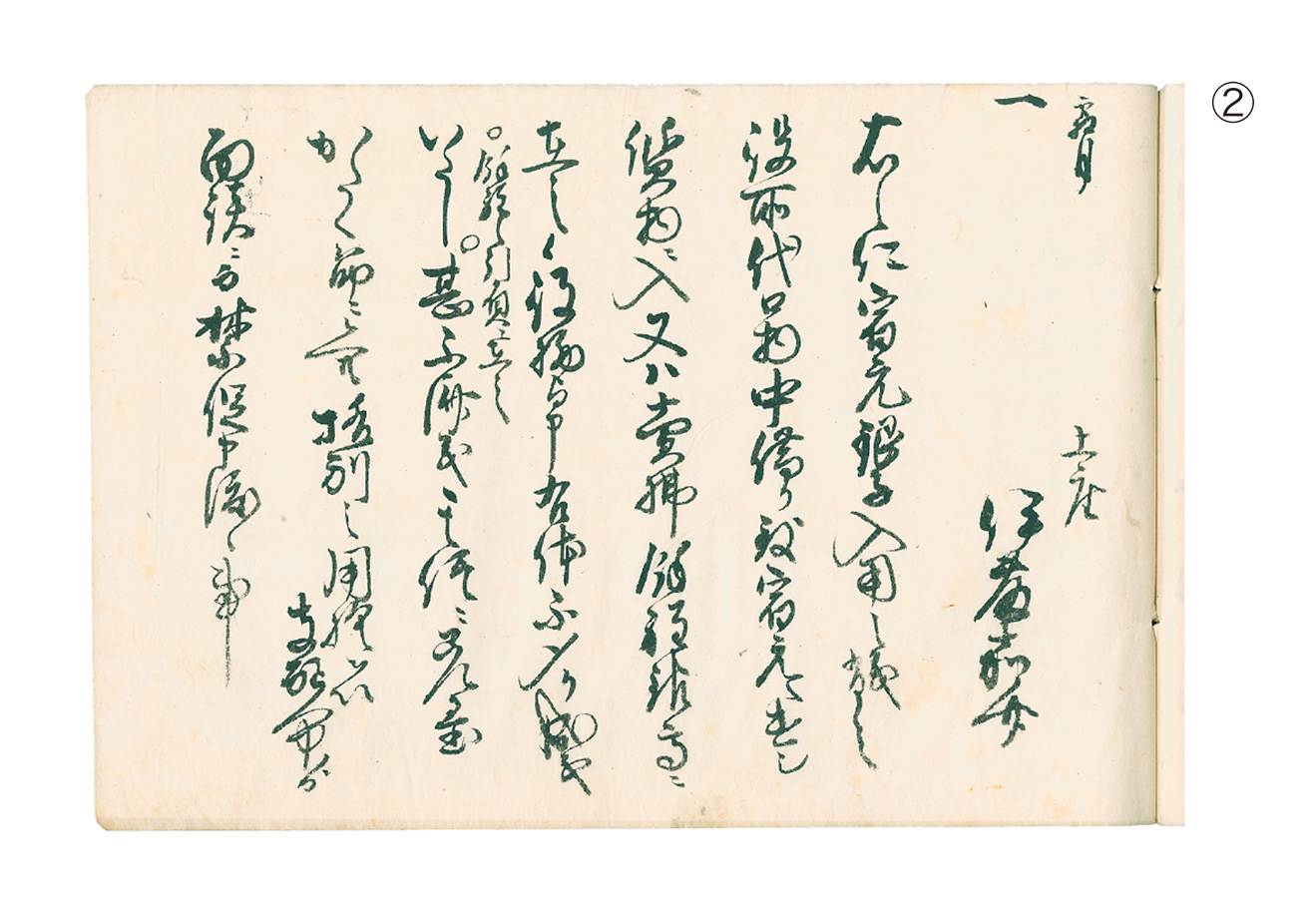

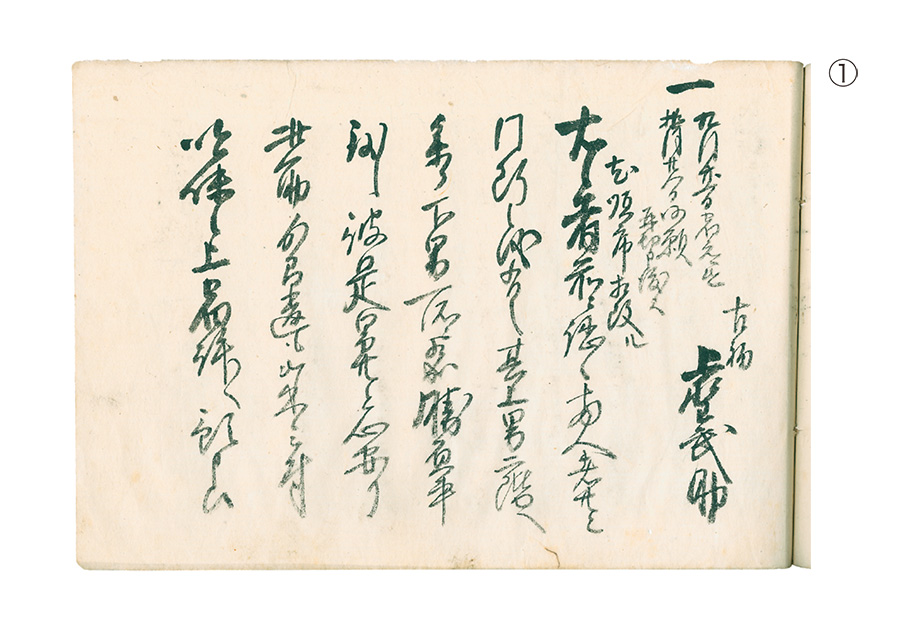

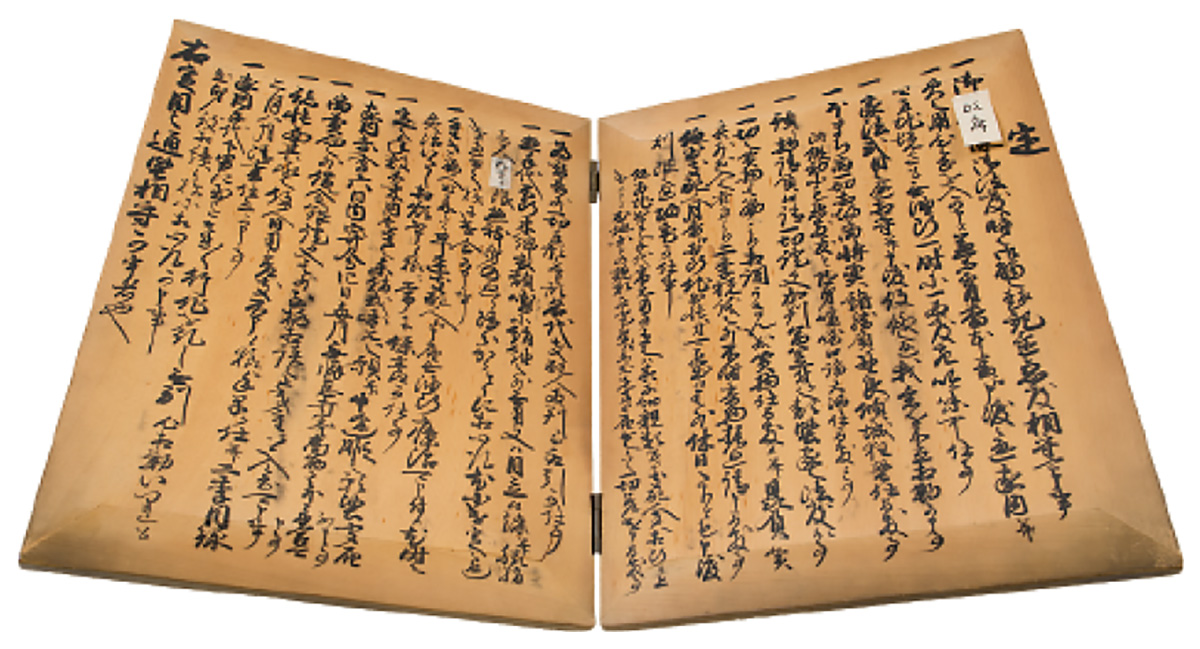

Employees had to follow a vast number of rules, of which several hundred are known. These rules reflected the size of the workforce to be managed and the complex nature of the business. There were rules for anything and everything-for young apprentices (graffiti was prohibited, bathing and hygiene areas were to be kept spotless, running indoors was forbidden, bedding was to be laid out and stowed quietly, etc.) all the way up to senior managers, who had to adhere to sales and personnel management policies, rules for handling important documents, etc. Rules were posted throughout the shop (→Fig. 20b), and were read aloud regularly to employees.

Many employees quit before being promoted to sales staff. It is thought that one reason for this was the number and severity of the regulations. Research interviews during the Meiji Era noted that training of younger employees was extremely strict.

Infractions and Their Management

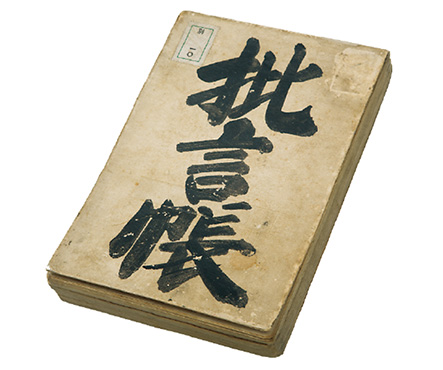

Many rules make for many infractions. The infractions record shown below preserves numerous examples of employee rule-breaking. The most common infraction was diversion and misappropriation of merchandise. Curfew was often violated. A clear picture of daily life under strict rules emerges, with employees taking every opportunity to leave the shop to visit the red-light district, enjoy drinking and eating, and generally spreading their wings. Such offences were dealt with meticulously according to the charges. Offenders were often forbidden from leaving the shop, required to perform night duty or, at worst, faced dismissal.

Absence from work was carefully recorded in units of time. At Kyoto kimono shop, those with spotless attendance or equivalent performance were given a monetary reward and were permitted to attend the festival at Fushimi Inari Shrine.

Some employees managed to achieve considerable success even while drawing repeated sanctions. The approach to discipline seems to have been more to educate employees than to act as a demerit system per se.

Bekke and Sozokuko

An employee with sufficient years of service and career success could establish his own residence and become an associate (bekke) with the right to use the Echigoya name and to place a split curtain (noren) at the entrance of his shop (→Fig. 20c). Some bekke employees went on commuting to the Mitsui shop from their residence, and senior managers basically followed this pattern. Bekke managing an independent business were not always successful. Mitsui Takafusa (→08) regarded this as a problem, and he established a mutual aid organization for such bekke (Sozokuko). Bekke with at least 20 years of service were eligible to join, and provided mutual consultation and assistance. Mitsui put up capital to fund financial assistance for bekke, and members of the Sozokuko paid membership dues that were deposited with Mitsui shops, where they gathered interest.

By around 1830, there were nearly 100 bekke playing important roles, both in Mitsui business and as a source for new employees.

This record was preserved by the Kyoto kimono shop. Entries include the employee’s name, the infraction, and any action taken, and were recorded by a senior employee.

The record profiles vividly such offenses as accounting irregularities and misappropriation, as well as the numerous problems that are part of collective living. This extremely valuable historical document paints a detailed portrait of the reality of life in the shops and of being an employee during the Edo period, a portrait that cannot be discerned from rules and regulations alone.

Unfortunately, only one such record survives, covering the years 1786 to 1805.

Translation

(Main entry) ① The individual named at right, in addition to previous offenses (visiting a brothel, misappropriation of funds), was found gambling in the manservants’ quarters. The cause of the problem is his over-familiarity with the manservants. After investigation he was sent back to his parents. (A note added to the beginning of the entry notes that he returned to his job three months later.)

② The individual named at right was diverting large amount of merchandise and selling it to help his parents. The offense is severe, but he was given special consideration and guidance from his supervisor, and confined to the shop.

Description

① related to gambling on shop premises, a typical problem of group living in a giant shop. Sales staff and manservants (→19) were warned not to fraternize.

② related to diversion of merchandise, another common offense at the time. Opportunities to leave the shop were valued by live-in employees, and confinement to the shop was thus a typical sanction.

Employee regulations were often written on a board like the one shown here, and posted in the shop. The board is hinged and can be folded to save space. The paper pasted to the board on the upper right replaces “shogunate” with “government” in the rule, “Abide by the laws of the shogunate.” This proves that the board was used into the Meiji Era.

This noren, to be hung over a shop entrance, was given to a bekke upon gaining the right to establish his own shop (noren wake). Detailed rules stipulated the precise type of curtain and where it could be used, depending on the employee’s rank.