17 Money Exchange Stores (2): Business Structure and Transition

The Ryogaedana Ichimaki Business

The principal business of the Ryogaedana Ichimaki, Mitsui’s financial division, was providing loans to merchants from the public funds of the shogunate, deposited in Osaka. Nominally, “deferred exchange” was to be arranged using these funds deposited in Osaka. For example, an exchange transaction might involve remitting payment owed by an Edo merchant to a merchant in Kyoto or Osaka, using funds borrowed from the shogunate’s treasury in Osaka. After a defined interval, Mitsui would collect the payment due from the Edo merchant, charging an exchange fee, and repay the shogunate by depositing the appropriate amount in the Edo Treasury (→16).But in the 18th century, Mitsui began making loans that had no actual relationship to currency exchange. Using the aforementioned mechanism, Mitsui lent funds, exceeding the amount entrusted to it, to merchants in the Kyoto-Osaka area and villages in the Kinai region, at high rates of interest. However, since the funds belonged to the shogunate as a matter of record, there were strong judicial protections for collection (→Fig. 17c) that were very favorable to Mitsui.

The Edo exchange store accepted deposits of public funds from sources such as the shogunate’s treasury, and used these funds to make large loans that were nominally investments. Later, loans made with real estate as collateral also became a major source of income. Many Osaka merchants funded their businesses with home mortgages, another source of funding that helped support Japan’s early modern economy.

Loans to feudal lords (daimyo) were a common way of investing large sums of money, but were not favored by Mitsui in view of the default risk, though the profits were reasonable (→09). With a few exceptions (→18), direct loans to daimyos were avoided, and risk was controlled with “deferred exchange” or mortgage loans, as described above, to a merchant designated by the daimyo.

As collateral for the deposit of public funds, Mitsui would take possession of the townhouse. It might also acquire a townhouse or farming village through foreclosure, and beginning in 1774, management of such assets was also assumed by the Ryogaedana Ichimaki.

Business Performance

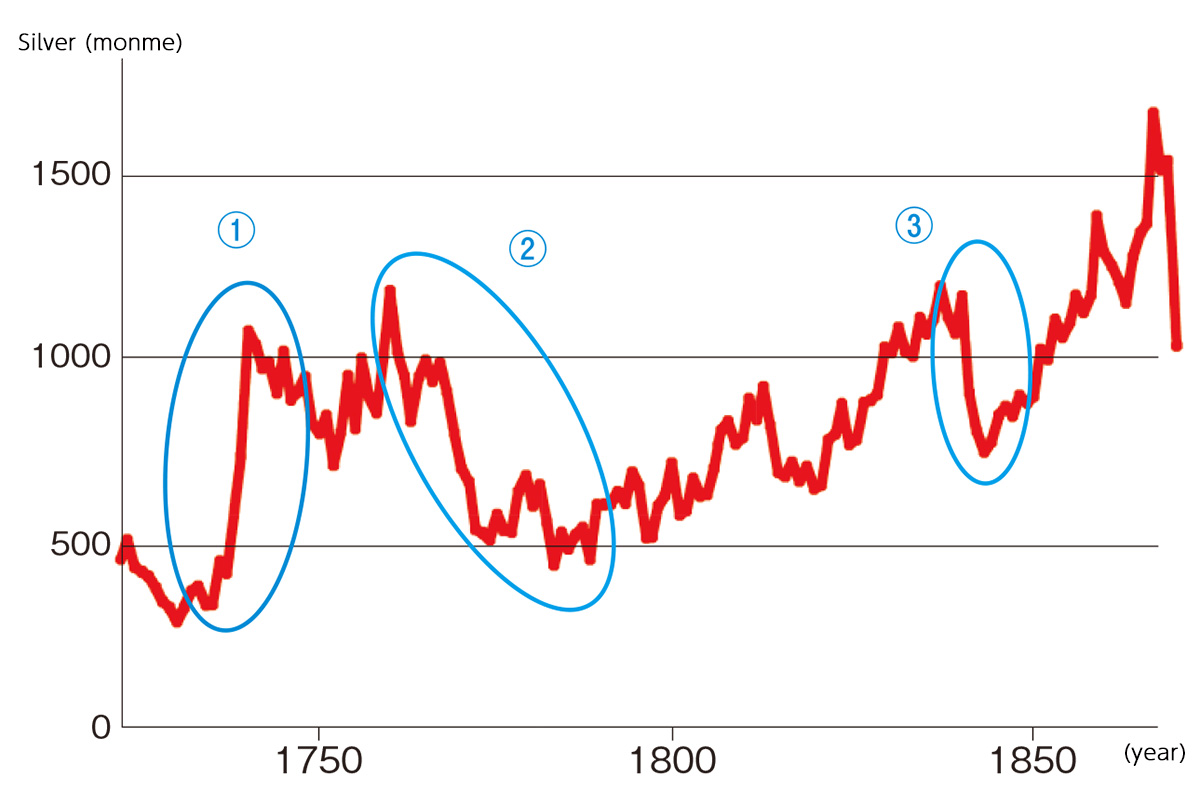

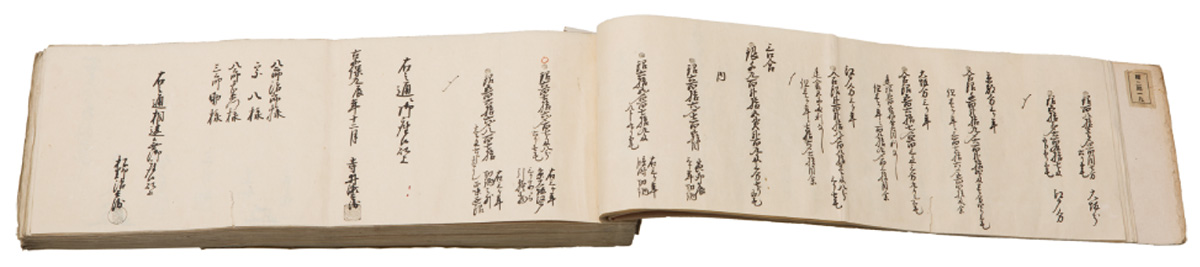

The Ryogaedana Ichimaki left extensive accounting records (→Fig. 17b), giving us a detailed picture of its management. Let’s take a closer look at its net profit (nobekin) over time (→Fig. 17d).

(1) Coming off the economic slump of the 1720s, profit rose quickly around the time of the currency reform of 1736 (→18), and reached its first peak in 1740.

(2) After the second peak in 1760, profit plunged in the late 1760s. A major factor is believed to have been the need to withdraw funds from more profitable investments to fund payments demanded by the Kishu Tokugawa family (→21).

(3) Thereafter, Mitsui worked to develop new borrowers in the Big Three cities, and profits rose year on year, though not dramatically. But in 1842, four years after profits reached a peak, they fell sharply in the wake of the Tenpo Reforms imposed by the shogunate and the resulting economic slump. Profits subsequently turned upward, reaching their final peak in 1868, in part due to a drop in the silver market.

Overall, profits were strong. The Kansei Unification (→10) fixed the required remittance to the Omotokata, with any profit beyond that accumulated as capital within the finance division. This was in sharp contrast to the situation in the Hondana Ichimaki (kimono division), where sales were largely flat (→12).

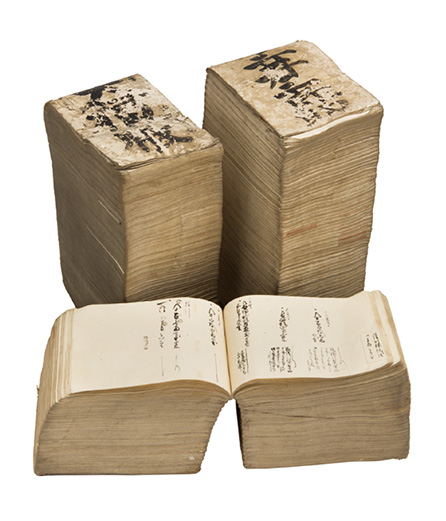

Merchants in the early modern period aggregated their accounts in a commercial ledger called the daifukucho, but the Mitsui ledgers of that name, shown here, record all transactions segregated into account categories. This approach is similar to modern general ledger accounting. Their approach to journaling sales transactions and adjustments was also close to today’s journal-based recordkeeping.

A sales journal was prepared by each Mitsui store twice annually. Sales journals survive from Kyoto (39), Osaka (160) and Edo (1). Numerous other types of accounting documents and supporting ledgers were used and managed meticulously.

Among Mitsui’s surviving historical documents, the exchange store daifukucho are voluminous, particularly ledgers from early Meiji-era Kyoto, some of which are over 40 centimeters thick. The three ledgers shown (left, right, and below) are each a single daifukucho.

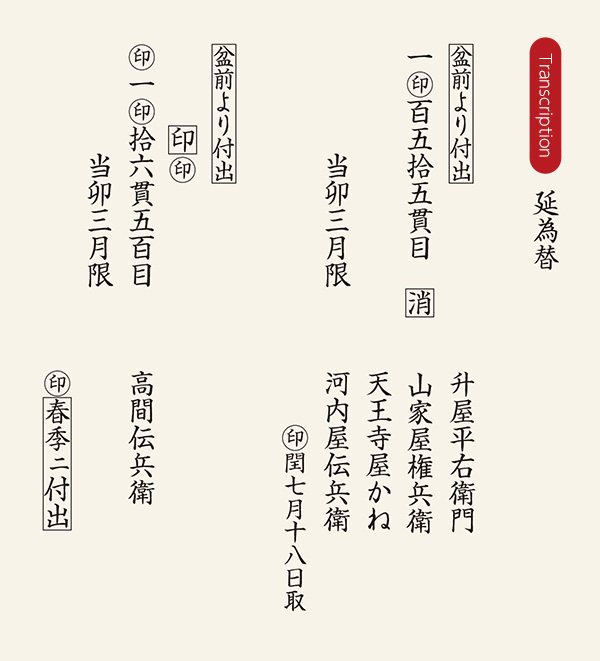

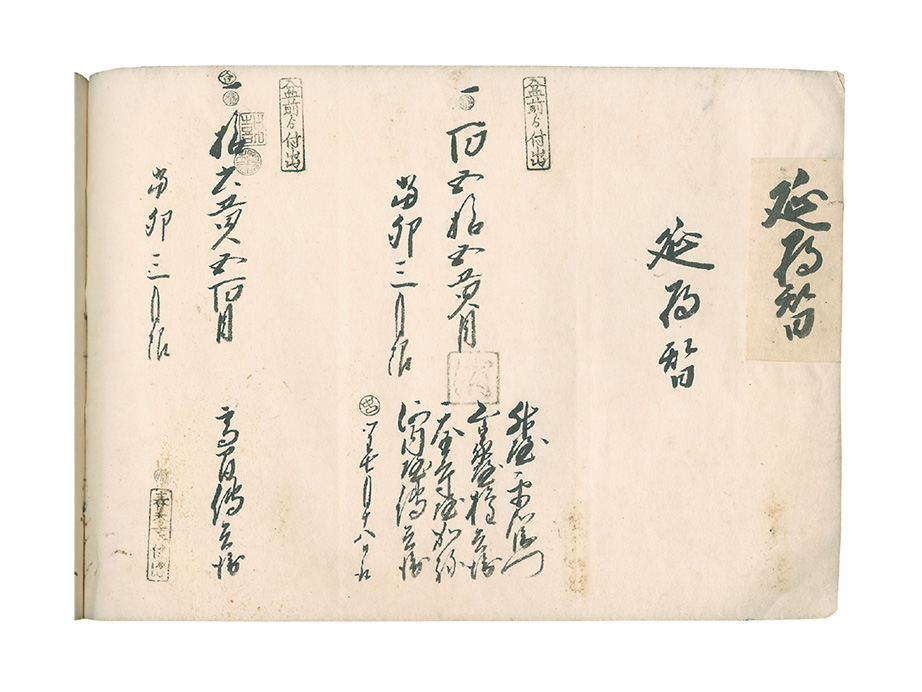

The sample page is from a sales ledger prepared by the Osaka exchange store for the second half of 1759, when financial division profits were trending upward. The ledger was designated to be held permanently at the exchange store.

Description

This is the first page of an entry for a “deferred exchange,” the account category for the financial division’s principal business. Two loans are recorded. One is to a well-known Osaka Dojima rice dealer, Masuya Heiemon. The other is to Takama Denbe, famous as one of the first wealthy merchants of Edo to become a target during civil unrest related to rice prices (→21).

Both transactions are marked with seals as continuing on from the previous half-year term. The deadline for payment is in the third month of the current year. The first loan is marked as having been repaid in the seventh month (intercalary), and has been marked as cancelled. No payments were received for the second loan during the term, and a seal confirms that it has been carried over to the ledger for the following term (half-year). Additional seals of various kinds indicate that accounting processes and audits had been conducted many times.

Financial statements of the Kyoto exchange store, for submission to the supervising Omotokata.

A record of lawsuits involving the Kyoto exchange store. Payments in arrears were common, and lawsuits were a regular occurrence, but Mitsui’s “deferred exchange” was protected by law, because on paper, they were an official service to the shogunate, with public funds being utilized in an exchange transaction.