12 Kimono Fabric Shops (1): Business Structure and Transition

The Big Three Cities and Product Distribution

As Japan moved into the 18th century, its goods economy began to grow in the “Big Three” cities of Kyoto, Edo, and Osaka. Kyoto became a logistics and processing center for raw materials and semi-finished goods; Edo became a distribution center for goods to meet urban consumer demand. Osaka became a principal node in the national distribution network, serving as a collection and distribution center for a wide range of goods from throughout the country.

Urban wholesalers supported the system of goods distribution centered on the Big Three cities. Wholesalers provided producers with the capital needed to produce goods, hire numerous craftsmen to process those goods, and supply the finished products to urban centers. They were the key to goods distribution in the Edo period, with networks reaching every corner of Japan.

In addition, wholesalers formed links with others in the same industry, joining hands to exclude outsiders and controlling the distribution of goods from purchasing and shipping to prices, under the imprimatur of the shogunate.

Echigoya’s Network of Shops

Echigoya, the kimono division of Mitsui, is generally known as a retailer, but it was also a silk fabric wholesaler, purchasing and processing fabrics at its Kyoto kimono shop before sending them on to the Edo kimono shop and the Muko and Shibaguchi shops, as well as the Osaka kimono shop, for retail sale. The Edo kimono shop was Echigoya’s largest in terms of floor space, total sales, number of employees, and other metrics. In Kyoto, the Kaminotana shop supplied the Kyoto kimono shop with Nishijin textiles. The Beni shop handled crimson silk dyeing. The Kanjoba (accounting office) supplied clothing for the shogunate, and in Edo there were shops such as the Itomise shop, purveyor of silk thread and other goods. The kimono division as a whole was known as Hondana Ichimaki. The “Hondana” shops in Edo and Osaka did not actually oversee the business of other Echigoya shops in the same city; they were simply standalone kimono shops.

The Kyoto kimono shop did not only procure goods, but supervised the eight retail shops. The Edo kimono shop in Surugacho was the most prominent Echigoya shop, but the Kyoto kimono shop was the administrative headquarters for the kimono division.

Echigoya participated in associations of kimono and cotton cloth wholesalers in Kyoto and Edo whose membership included names like Daimaru, Ebisuya, and Shirokiya (→14).

Echigoya’s Sales

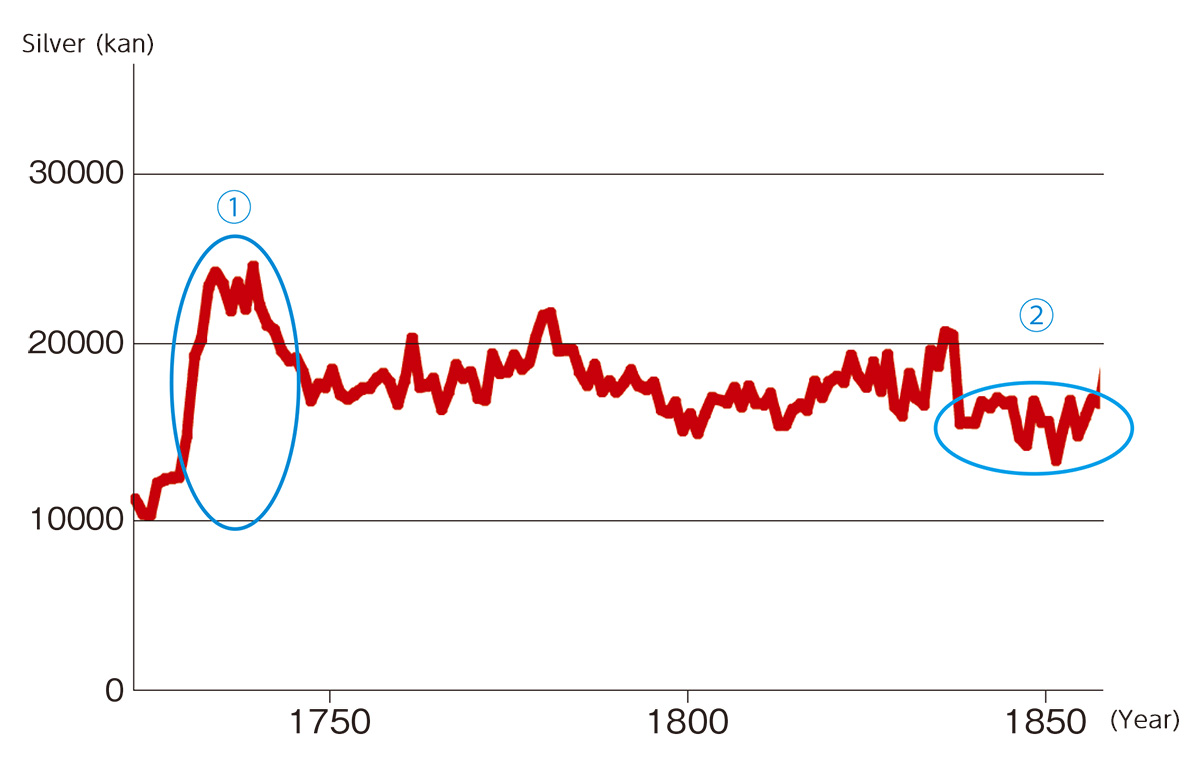

Let us take a closer look at total sales of the kimono division, the most important indicator of Echigoya’s success. The graph summarizes total sales over approximately 130 years, from 1729 to 1861 (→Fig. 12c). The data includes two major areas of interest.

(1) Sales of the kimono division rose during this period. Except for a bout of inflation at the end of the Edo period, it is said that 1745 was the peak year for Echigoya’s sales. For example, Edo kimono shop sales reached 13,800 kan of silver, and remained high throughout the period. The Edo Muko shop and Osaka kimono shop also enjoyed favorable sales. Echigoya achieved its greatest success relatively early in its long history, with positive influence from the rise in goods prices due to the shogunate’s currency reform of the 1730s (→18) and strong sales in response to the greatly discounted prices it advertised.

While sales subsequently declined, they continued at roughly consistent levels until the 1830s.

(2) Sales fell during this period. Causative factors included the Tenpo Reforms, which depressed sales of high-end kimonos through sumptuary edicts.

Inflation during the last years of the shogunate drove nominal sales figures sharply upward, but the gains were illusory.

On the expense side, after period (1), Echigoya struggled to survive as the balance of uncollected consumer debts from credit sales grew. In addition, its shops suffered from repeated fires (→21) and consequent major reconstruction costs. The years during and after the Tenpo era (2), which begam in 1830, were particularly challenging.

These hanging scrolls depict (from right) Echigoya shops in Kyoto, Edo, and Osaka. Artist and dates are unknown, but the scrolls are thought to be from the first half of the 19th century, and give us a rare glimpse of three shops in three cities at the same time. Because the Kyoto shop was an administrative base and distribution point, it is plain and unadorned, while the Edo and Osaka shops are decked out with curtains that beckon to customers, and present a flashy appearance.

This record of operations was maintained by senior managers in the Kyoto kimono shop. Twenty-eight volumes have been preserved, spanning approximately 140 years from 1737 to 1871. These chronological records cover a wide range of subjects, from the doings of employees and the management situation at each shop to details of damage inflicted on the business by fires. The Kyoto kimono shop also has a series of journals named “Eisho,” and these are primary source for research into the history of the kimono division.